Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence (1821–1829), also commonly known as the Greek Revolution was a successful war waged by the Greeks to win independence for Greece from the Ottoman Empire. After a long and bloody struggle, and with the aid of the Great Powers, independence was finally granted by the Treaty of Constantinople in July 1832. The Greeks were thus the first of the Ottoman Empire’s subject peoples to secure recognition as an independent sovereign power. The anniversary of Independence Day (March 25, 1821) is a National Day in Greece, which falls on the same day as the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary. European support was critical but not unambiguous in aiding the revolution. A mix of romanticism about Ancient Greece as the inspiration behind much European art, philosophy and culture, Christian animosity towards Islam and sheer envy of the Ottomans combined to compel the great powers to rally to the Hellenic cause.

The Greek War of Independence (1821–1829), also commonly known as the Greek Revolution was a successful war waged by the Greeks to win independence for Greece from the Ottoman Empire. After a long and bloody struggle, and with the aid of the Great Powers, independence was finally granted by the Treaty of Constantinople in July 1832. The Greeks were thus the first of the Ottoman Empire’s subject peoples to secure recognition as an independent sovereign power. The anniversary of Independence Day (March 25, 1821) is a National Day in Greece, which falls on the same day as the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary. European support was critical but not unambiguous in aiding the revolution. A mix of romanticism about Ancient Greece as the inspiration behind much European art, philosophy and culture, Christian animosity towards Islam and sheer envy of the Ottomans combined to compel the great powers to rally to the Hellenic cause.

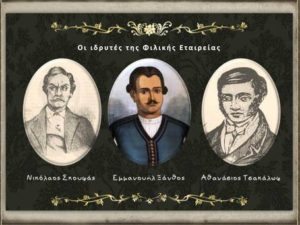

Preparation for the uprising—The Filiki Eteria

In 1814, three Greek merchants, Nikolaos Skoufas, Manolis Xanthos, and Athanasios Tsakalov, inspired by the ideas of Feraios and influenced by the Italian Carbonari, founded the secret Filiki Eteria (“Society of Friends”), in Odessa, an important centre of the Greek mercantile diaspora. With the support of wealthy Greek exile communities in Great Britain and the United States and the aid of sympathisers in Western Europe, they planned the rebellion. The basic objective of the society was a revival of the Byzantine Empire, with Constantinople as the capital, not the formation of a national state. In early 1820, Ioannis Kapodistrias, an official from the Ionian Islands who had become the Russian Foreign Minister, was approached by the Society to be named leader but declined the offer; the Filikoi (members of Filiki Eteria) then turned to Alexander Ypsilantis, a Phanariote serving in the Russian army as general and adjutant to Tsar Alexander I, who accepted.

In 1814, three Greek merchants, Nikolaos Skoufas, Manolis Xanthos, and Athanasios Tsakalov, inspired by the ideas of Feraios and influenced by the Italian Carbonari, founded the secret Filiki Eteria (“Society of Friends”), in Odessa, an important centre of the Greek mercantile diaspora. With the support of wealthy Greek exile communities in Great Britain and the United States and the aid of sympathisers in Western Europe, they planned the rebellion. The basic objective of the society was a revival of the Byzantine Empire, with Constantinople as the capital, not the formation of a national state. In early 1820, Ioannis Kapodistrias, an official from the Ionian Islands who had become the Russian Foreign Minister, was approached by the Society to be named leader but declined the offer; the Filikoi (members of Filiki Eteria) then turned to Alexander Ypsilantis, a Phanariote serving in the Russian army as general and adjutant to Tsar Alexander I, who accepted.

The Filiki Eteria rapidly expanded, gaining members in almost all regions of Greek settlement, amongst them figures who would later play a prominent role in the war, such as Theodoros Kolokotronis, Odysseas Androutsos, Papaflessas and Laskarina Bouboulina. In 1821, the Ottoman Empire found itself occupied with war against Persia and most particularly with the revolt by Ali Pasha in Epirus, which had forced the vali (governor) of the Morea, Hursid Pasha, and other local pashas to leave their provinces and campaign against the rebel force. At the same time, the Great Powers, allied in the “Concert of Europe” in their opposition to revolutions in the aftermath of Napoleon I of France, were preoccupied with revolts in Italy and Spain. It was in this context that the Greeks judged the time to be ripe for their own revolt. The plan originally involved uprisings in three places, the Peloponnese, the Danubian Principalities and Constantinople. The start of the uprising can be traced to on February 22 1821 (O.S.), when Alexander Ypsilantis and several other Greek officers of the Russian army crossed the river Prut into Moldavia.

Philhellenism

Due to Greece’s classical heritage, there was tremendous sympathy for the Greek cause throughout Europe. Many wealthy Americans and Western European aristocrats, such as the renowned poet Lord Byron, took up arms to join the Greek revolutionaries. Many more also financed the revolution. The Scottish historian and philhellene Thomas Gordon took part in the revolutionary struggle and later wrote the first histories of the Greek revolution in English. Use of the term “Turkish yoke” in his title reflects the popular view that the Ottomans were tyrants who exploited and oppressed their subjects, who were therefore fully justified to revolt. Rebellion against oppression may indeed be just cause for revolt but few in Europe drew parallels between how their empires treated their own subjects, even though the British had experienced the successful revolt of their 12 North American colonies and numerous revolts in Ireland. Gordon wrote of how the Greeks were “accustomed from their infancy to tremble at the sight of a Turk” while “ruin and depopulation were pressing on these hardy mountaineers” whose “hatred of their tyrants” was “untamed.”

Due to Greece’s classical heritage, there was tremendous sympathy for the Greek cause throughout Europe. Many wealthy Americans and Western European aristocrats, such as the renowned poet Lord Byron, took up arms to join the Greek revolutionaries. Many more also financed the revolution. The Scottish historian and philhellene Thomas Gordon took part in the revolutionary struggle and later wrote the first histories of the Greek revolution in English. Use of the term “Turkish yoke” in his title reflects the popular view that the Ottomans were tyrants who exploited and oppressed their subjects, who were therefore fully justified to revolt. Rebellion against oppression may indeed be just cause for revolt but few in Europe drew parallels between how their empires treated their own subjects, even though the British had experienced the successful revolt of their 12 North American colonies and numerous revolts in Ireland. Gordon wrote of how the Greeks were “accustomed from their infancy to tremble at the sight of a Turk” while “ruin and depopulation were pressing on these hardy mountaineers” whose “hatred of their tyrants” was “untamed.”

Lord Byron was a prominent English philhellene who died during the Greek revolution

Once the revolution broke out, Ottoman atrocities were given wide coverage in Europe, including also by Eugene Delacroix, and drew sympathy for the Greek cause in Western Europe, although for a time the British and French governments suspected that the uprising was a Russian plot to seize Greece (and possibly Constantinople) from the Ottomans. The Greeks were unable to establish a coherent government in the areas they controlled, and soon fell to fighting among themselves. Inconclusive fighting between Greeks and Ottomans continued until 1825, when Sultan Mahmud II asked for help from his most powerful vassal, Egypt.

In Europe, the Greek revolt aroused widespread sympathy among the public but was met at first with the lukewarm reception above from the Great Powers, with Britain then backing the insurrection from 1823 onward, after Ottoman weakness was clear, despite the opportunities offered it by Greek civil conflict and the addition of Russian support aimed at limiting British influence over the Greeks. Greece was viewed as the cradle of western civilization, and it was especially lauded by the spirit of romanticism of the time and the sight of a Christian nation attempting to cast off the rule of a decaying Muslim Empire also found favour amongst the western European public, although few knew very much about the Eastern Orthodox Church.

In Europe, the Greek revolt aroused widespread sympathy among the public but was met at first with the lukewarm reception above from the Great Powers, with Britain then backing the insurrection from 1823 onward, after Ottoman weakness was clear, despite the opportunities offered it by Greek civil conflict and the addition of Russian support aimed at limiting British influence over the Greeks. Greece was viewed as the cradle of western civilization, and it was especially lauded by the spirit of romanticism of the time and the sight of a Christian nation attempting to cast off the rule of a decaying Muslim Empire also found favour amongst the western European public, although few knew very much about the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Lord Byron spent time in Albania and Greece, organising funds and supplies (including the provision of several ships), but died from fever at Messolonghi in 1824. Byron’s death did even more to add European sympathy for the Greek cause. This eventually led the Western powers to intervene directly. Byron’s poetry, along with Delacroix’s art, helped arouse European public opinion in favour of the Greek revolutionaries:

The mountains look on Marathon—

And Marathon looks on the sea;

And musing there an hour alone,

I dream’d that Greece might yet be free

For, standing on the Persians’ grave,

I could not deem myself a slave.

…

Must we but weep o’er days more blest?

Must we but blush?—Our fathers bled.

Earth! render back from out thy breast

A remnant of our Spartan dead!

Of the three hundred grant but three,

To make a new Thermopylae.

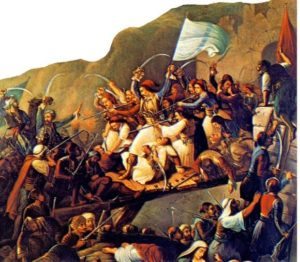

Outbreak of the Revolution

The Revolution in the Danubian Principalities

Alexander Ypsilantis was the selected as the head of the Filiki Eteria in April 1820, and set himself the task of planning the insurrection. Ypsilantis’ intention was to raise all the Christians of the Balkans in rebellion, and perhaps force Russia to intervene on their behalf. On February 22, 1821, he crossed the river Prut with his followers, entering the Danubian Principalities, while in order to encourage the local Romanian Christians to join him, he announced that he had “the support of a Great Power,” implying Russia. Two days after crossing the Prut, on the February 24, Ypsilantis issued a proclamation calling on all Greeks and Christians to rise up against the Ottomans:

Alexander Ypsilantis was the selected as the head of the Filiki Eteria in April 1820, and set himself the task of planning the insurrection. Ypsilantis’ intention was to raise all the Christians of the Balkans in rebellion, and perhaps force Russia to intervene on their behalf. On February 22, 1821, he crossed the river Prut with his followers, entering the Danubian Principalities, while in order to encourage the local Romanian Christians to join him, he announced that he had “the support of a Great Power,” implying Russia. Two days after crossing the Prut, on the February 24, Ypsilantis issued a proclamation calling on all Greeks and Christians to rise up against the Ottomans:

“Fight for Faith and Motherland! The time has come, O Hellenes. Long ago the people of Europe, fighting for their own rights and liberties, invited us to imitation… The enlightened peoples of Europe are occupied in restoring the same well-being, and, full of gratitude for the benefactions of our forefathers towards them, desire the liberation of Greece. We, seemingly worthy of ancestral virtue and of the present century, are hopeful that we will achieve their defence and help. Many of these freedom-lovers want to come and fight alongside us…. Who then hinders your manly arms? Our cowardly enemy is sick and weak. Our generals are experienced, and all our fellow countrymen are full of enthusiasm. Unite, then, O brave and magnanimous Greeks! Let national phalanxes be formed, let patriotic legions appear and you will see those old giants of despotism fall by themselves, before our triumphant banners.”

Instead of directly advancing on Brăila, where he arguably could have prevented Ottoman armies from entering the Principalities, and where he might have forced Russia to accept a fait accompli, he remained in Iaşi, and ordered the executions of several pro-Ottoman Moldovans. In Bucharest, where he had arrived on March 27 after some weeks delay, he decided that he could not rely on the Wallachian Pandurs to continue their Oltenian-based revolt and assist the Greek cause; Ypsilantis was mistrusted by the Pandur leader Tudor Vladimirescu, who, as a nominal ally to the Eteria, had started the rebellion as a move to prevent Scarlat Callimachi from reaching the throne in Bucharest, while trying to maintain relations with both Russia and the Ottomans.

At that point, former Russian Foreign Minister, the Corfu-born Greek Ioannis Kapodistrias, sent Ypsilantis a letter upbraiding him for misusing the mandate received from the Tsar, announcing that his name had been struck off the army list, and commanding him to lay down arms. Ypsilantis tried to ignore the letter, but Vladimirescu took this to mean that his commitment to the Eteria was over. A conflict erupted inside his camp, and he was tried and put to death by the Eteria on May 27. The loss of their Romanian allies followed an Ottoman intervention on Wallachian soil sealed defeat for the Greek exiles, culminating in the disastrous Battle of Dragashani and the destruction of the Sacred Band on June 7.

Alexander Ypsilantis, accompanied by his brother Nicholas and a remnant of his followers, retreated to Râmnic, where he spent some days negotiating with the Austrian authorities for permission to cross the frontier. Fearing that his followers might surrender him to the Turks, he gave out that Austria had declared war on Turkey, caused a Te Deum to be sung in the church of Cozia, and, on pretext of arranging measures with the Austrian commander-in-chief, he crossed the frontier. But the reactionary policies of the Holy Alliance were enforced by Emperor Francis I and the country refused to give asylum for leaders of revolts in neighbouring countries. Ypsilantis was kept in close confinement for seven years. In Moldavia, the struggle continued for a while, under Giorgakis Olympios and Yiannis Pharmakis, but by the end of the year, the provinces had been pacified by the Ottomans.

The Revolution in the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese, with its long tradition of resistance to the Ottomans, was to be the heartland of the revolt. In the early months of 1821, with the absence of the Turkish governor Mora valesi Hursid Pasha and many of his troops, the situation was favourable for the Greeks to rise against Ottoman occupation. Theodoros Kolokotronis, a renowned Greek klepht who had served in the British army in the Ionian Islands during the Napoleonic Wars, returned on January 6, 1821, and went to the Mani Peninsula. The Turks found out about Kolokotronis’ arrival, and demanded his surrender from the local bey, Petros Mavromichalis, also known as Petrobey. Mavromichalis refused, saying he was just an old man.

The Peloponnese, with its long tradition of resistance to the Ottomans, was to be the heartland of the revolt. In the early months of 1821, with the absence of the Turkish governor Mora valesi Hursid Pasha and many of his troops, the situation was favourable for the Greeks to rise against Ottoman occupation. Theodoros Kolokotronis, a renowned Greek klepht who had served in the British army in the Ionian Islands during the Napoleonic Wars, returned on January 6, 1821, and went to the Mani Peninsula. The Turks found out about Kolokotronis’ arrival, and demanded his surrender from the local bey, Petros Mavromichalis, also known as Petrobey. Mavromichalis refused, saying he was just an old man.

The crucial meeting was held at Vostitsa (modern Aigion), where chieftains and prelates from all over the Peloponnese assembled on January 26. There the klepht captains declared their readiness for the uprising, while most of the civil leaders presented themselves sceptical, and demanded guarantees about a Russian intervention. Nevertheless, as news came of Ypsilantis’ march into the Danubian Principalities, the atmosphere in the Peloponnese was tense, and by mid-March, sporadic incidents against Muslims occurred, heralding the start of the uprising. The traditional legend that the Revolution was declared on March 25 in the Monastery of Agia Lavra by the archbishop of Patras Germanos is a later invention. However, the date has been established as the official anniversary of the Revolution, and is celebrated as a national day in Greece.

On March 17, 1821, war was declared on the Turks by the Maniots at Areopoli. An army of 2,000 Maniots under the command of Petros Mavromichalis, which included Kolokotronis, his nephew Nikitaras and Papaflessas advanced on the Messenian town of Kalamata. The Maniots reached Kalamata on March 21 and after a brief two day siege it fell to the Greeks on the 23rd. On the same day, Andreas Londos, a Greek primate, rose up at Vostitsa. On March 28, the Messenian Senate, the first of the Greeks’ local governing councils, held its first session at Kalamata.

In Achaia, the town of Kalavryta was besieged on March 21. In Patras, in the already tense atmosphere, the Ottomans had transferred their belongings to the fortress on February 28, followed by their families on March 18. On March 22, the revolutionaries declared the Revolution in the square of Agios Georgios in Patras, in the presence of archbishop Germanos. On the next day the leaders of the Revolution in Achaia sent a document to the foreign consulates explaining the reasons of the Revolution. On March 23, the Ottomans launched sporadic attacks towards the town while the revolutionaries, led by Panagiotis Karatzas, drove them back to the fortress. Yannis Makriyannis who had been hiding in the town referred to the scene in his memoirs:

Σε δυο ημέρες χτύπησε ντουφέκι στην Πάτρα. Οι Tούρκοι κάμαν κατά το κάστρο και οι Ρωμαίγοι την θάλασσα.

Shooting broke out two days later in Patras. The Turks had seized the fortress, and the Romans (Greeks) had taken the seashore.

By the end of March, the Greeks effectively controlled the countryside, while the Turks were confined to the fortresses, most notably those of Patras, Rio, Acrocorinth, Monemvasia, Nafplion and the provincial capital, Tripolitsa, where many Muslims had fled with their families at the beginning of the uprising. All these were loosely besieged by local irregular forces under their own captains, since the Greeks lacked artillery. With the exception of Tripolitsa, all sites had access to the sea and could be resupplied and reinforced by the Ottoman fleet.

Kolokotronis, determined to take Tripolitsa, the Ottoman provincial capital in the Peloponnese, moved into Arcadia with 300 Greek soldiers. When he entered Arcadia his band of 300 fought a Turkish force of 1,300 men and defeated them. On April 28, few thousand Maniot soldiers under the command of Mavromichalis’ sons joined Kolokotronis’ camp outside Tripoli. On September 12, 1821, Tripolitsa was captured by Kolokotronis and his men.

The revolution in central Greece

The first region to revolt in Central Greece was Phocis, on March 24, whose capital, Salona (modern Amfissa), was captured by Panourgias on March 27. In Boeotia, Livadeia was captured by Athanasios Diakos on March 29, followed by Thebes two days later. The Ottoman garrison held out in the citadel of Salona, the regional capital, until April 10, when the Greeks took it. At the same time, the Greeks suffered a defeat at the Battle of Alamana against the army of Omer Vryonis, which resulted in the death of Athanasios Diakos. But the Ottoman advance was stopped at the Battle of Gravia, near Mount Parnassus and the ruins of ancient Delphi, under the leadership of Odysseas Androutsos. Vryonis turned towards Boeotia and sacked Livadeia, awaiting reinforcements before proceeding towards the Morea. These forces, 8,000 men under Beyran Pasha, were however met and defeated at the Battle of Vassilika, on August 26. This defeat forced Vryonis to withdraw, securing the fledgling Greek revolutionaries.

The first region to revolt in Central Greece was Phocis, on March 24, whose capital, Salona (modern Amfissa), was captured by Panourgias on March 27. In Boeotia, Livadeia was captured by Athanasios Diakos on March 29, followed by Thebes two days later. The Ottoman garrison held out in the citadel of Salona, the regional capital, until April 10, when the Greeks took it. At the same time, the Greeks suffered a defeat at the Battle of Alamana against the army of Omer Vryonis, which resulted in the death of Athanasios Diakos. But the Ottoman advance was stopped at the Battle of Gravia, near Mount Parnassus and the ruins of ancient Delphi, under the leadership of Odysseas Androutsos. Vryonis turned towards Boeotia and sacked Livadeia, awaiting reinforcements before proceeding towards the Morea. These forces, 8,000 men under Beyran Pasha, were however met and defeated at the Battle of Vassilika, on August 26. This defeat forced Vryonis to withdraw, securing the fledgling Greek revolutionaries.

The revolution in Crete

Cretan participation in the revolution was extensive, but it failed to achieve liberation from Turkish rule due to Egyptian intervention. Crete had a long history of resisting Turkish rule, exemplified by the folk hero Daskalogiannis who was martyred whilst fighting the Turks. In 1821, an uprising by Christians met with a fierce response from the Ottoman authorities and the execution of several bishops, regarded as ringleaders. Between 1821 and 1828, the island was the scene of repeated hostilities and atrocities. The Muslims were driven into the large fortified towns on the north coast and it would appear that as many as 60 percent of them died from plague or famine while there. The Cretan Christians also suffered severely, losing around 21 percent of their population.

Cretan participation in the revolution was extensive, but it failed to achieve liberation from Turkish rule due to Egyptian intervention. Crete had a long history of resisting Turkish rule, exemplified by the folk hero Daskalogiannis who was martyred whilst fighting the Turks. In 1821, an uprising by Christians met with a fierce response from the Ottoman authorities and the execution of several bishops, regarded as ringleaders. Between 1821 and 1828, the island was the scene of repeated hostilities and atrocities. The Muslims were driven into the large fortified towns on the north coast and it would appear that as many as 60 percent of them died from plague or famine while there. The Cretan Christians also suffered severely, losing around 21 percent of their population.

As the Ottoman sultan, Mahmud II, had no army of his own, he was forced to seek the aid of his rebellious vassal and rival, the Pasha of Egypt, who sent troops into the island. Britain decided that Crete should not become part of the new Kingdom of Greece on its independence in 1830, evidently fearing that it would either become a centre of piracy as it had often been in the past, or a Russian naval base in the East Mediterranean. Crete would remain under Ottoman suzerainty, but Egyptians administered the island, such as the Egyptian-Albanian Giritli Mustafa Naili Pasha.

Source: New World Encyclopedia